BOWENS ISLAND

If you wanted to make May Bowen mad, ask for a condiment. Yet filling every inch of wall and table space in her little restaurant with graffiti, that she didn’t mind. It sort of blended in with the broken TVs and chairs of every description lying around. The toilets were outside, sans electricity but with plenty of bugs and the occasional snake. It was said that Bowens Island was not so much a restaurant as a state of mind. Perhaps that’s why Patricia Schultz included it in her first edition of 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. Or perhaps it was the great seafood (which Miss May wasn’t going to let you ruin with condiments), pulled fresh from Charleston’s waterways.

She and her husband, Jimmy, bought the 14-acre island in 1946 intending to retire from their restaurant on Folly Beach. They wanted to open a fish camp, so they built a dock, a cabin, a dirt causeway, and a 20’ by 40’ cinderblock shed where they sold tackle, bait, soft drinks and snacks. Fishermen began asking Miss May if she would fry up some of their catch. Before they knew it, they were back in the restaurant business.

At Bowens, it was Miss May, not the customer, who was always right. Anyone criticizing the food was told to leave. Yet those who knew her best recognized a good-hearted woman lay beneath the crusty exterior. On Sundays she fed lonely servicemen from Charleston’s Naval Yard home-cooked meals. One, John Sanka, eventually just stayed and became the chef.

Miss May, Jimmy and John were a unique threesome, grandson Robert Barber told Amy Evans in an interview for the Southern Foodways Alliance Oral Histories project in 2007. They had no menus, serving only shrimp, crab cakes, fish, and occasionally fried chicken, all with hushpuppies. No French fries, grits or vegetables. Everything was cooked in the same frying pan.

Yet Bowens’ claim to fame was its all-you-can-eat oysters, dumped by the shovel full onto your table in a room with a dirt floor. No one got into the oyster room without paying to be in there. If you were the only person in your party not eating oysters, you ate alone. In 1971, oysters cost $3, customer Duke Eversmeyer told Evans. “Mr. Bowen would hang around and when he thought you’d eaten your $3 worth he’d tell you about his cornea transplant, describing it in great detail.” After that, he said, you didn’t want any more oysters.

Miss May died in 1990 on Bowens’ front porch shortly before the dinner crowd arrived. Barber, a lawyer, ordained minister and former member of the S.C. House of Representatives, had worked closely with his grandmother. He put everything else aside to keep her restaurant going. He updated the building, adhering more closely to the state’s health and safety regulations (e.g. indoor bathrooms and no more dirt floors), added modern kitchen equipment and expanded the menu.

In May 2006, all the hard work by Barber, his grandparents, John Sanka, and the fishermen who had become part of the Bowens family was recognized with a coveted James Beard Award as an “American Classic.” Five months later, during the evening of October 22, the restaurant burned to the ground, presumably the victim of faulty wiring. Two weeks after that, Barber lost the state’s Lieutenant Governor’s race, 545,414 to 540,307. In a thank-you letter to his supporters, Barber ended by saying “…excuse me now. I’ve got a restaurant to run.” He continues to do so.

Sources & More Information

Schultz, Patricia. 1,000 Places to See Before You Die.

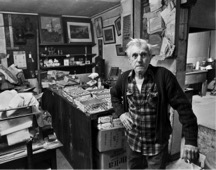

Chef John Sanka

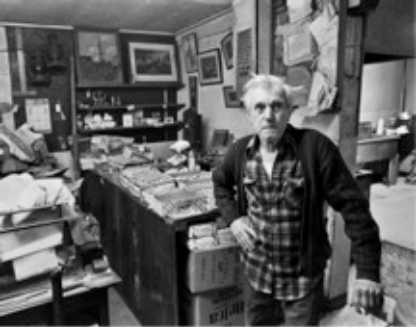

The First Lady of Bowens Island May Bowen.

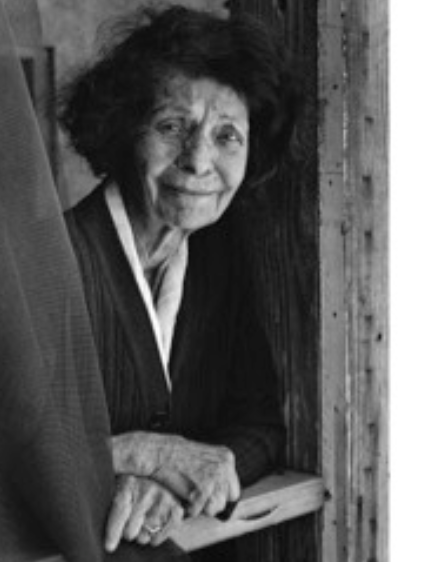

The oyster room