DUELING: AN AFFAIR OF HONOR

As temperatures rose in pre-20th century Charleston, so did tempers. Charleston's past includes a great many duels from June until September; July was a popular month for the once-legal method of settling disagreements. Defending one's honor through the Code Duello was no small matter.

One of the most famous duels in American history is that of Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, which took place on July 11, 1804. The Broadway musical “Hamilton” has reacquainted us with the tragic story of these founding fathers and Revolutionary War heroes in which Burr, the nation’s third vice president, mortally wounded its first secretary of treasury.

Though illegal in New Jersey where their confrontation took place, dueling was an accepted practice in 18th- and 19th-century Charleston. Dr. David Ramsay (1749–1815) blamed Charlestonians’ propensity for dueling on the climate, saying “warm weather and its attendant increase of bile in the stomach” caused “an irritable temper which made men say and do things thoughtlessly.”

Dueling was how upper-class gentlemen — and though rarely, even women — settled disputes and avenged insults. Issuing or accepting an invitation to duel was considered proof that one knew he was right and was willing to put his life on the line to prove it. To refuse a challenge gave credence to an accusation, marking one as a coward and liar.

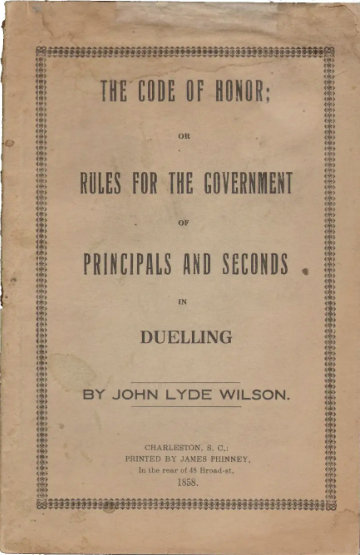

In Charleston, challenges were governed by the code duello, a strict protocol based on an old Irish code and formalized by former S.C. Gov. John Lyde Wilson in 1838. Because of the code’s safeguards, duels, while not uncommon, were rarely fought to the death. First, it required that avenues of compromise be exhausted before resorting to violence, helping lessen crimes of passion at a time when all White men carried firearms.

Friends or family members known as “seconds” were appointed for each party to seek a mutual understanding or retraction of the accusation. Most disputes were settled this way once tempers cooled and everybody had a night or two to sleep on things.

Second, dueling at an established place and time ensured physicians could be present, as could witnesses to attest to facts of the confrontation, minimizing gossip.

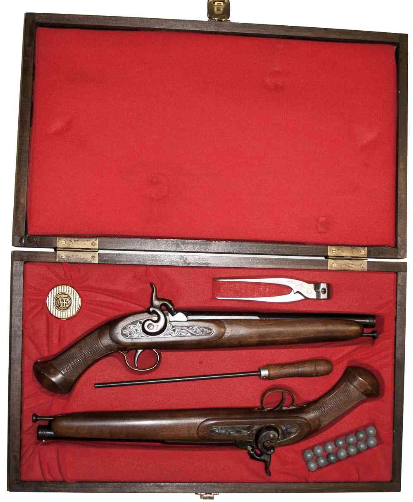

Third, the code ensured the duel was fought fairly. One party selected the pair of weapons while the other had first pick of the pair. Seconds inspected the weapons to ensure they had not been tampered with.

Finally, if matters reached this point without resolution, opponents had a final opportunity to look each other in the eye in a calmer, more controlled light days after the offense and reconsider whether they were committed enough to their position to risk injury, death or murder. If so, then each party was allowed one shot upon the second’s command.

Now this is the important part: The code duello provided a loophole. Duelers could purposely miss their shot, avoiding injury or death to their opponent. If both did, their honors were restored because each had risked his life to defend his word. This option was common, but unfortunately not absolute, as in the case of Burr and Hamilton.

If either man were wounded even slightly, the duel could be over and the requirements fulfilled for restoring each man’s honor. However, the wounded party could call for a second round of shots. This, as you might guess, didn’t happen often. In the worst cases, if one party failed to abide by the code or cheated in any way, the second could shoot the offender from the sidelines — and, in the very rarest cases, even each other.

Details about the Burr/Hamilton duel are contested even today. Burr was vilified and charged with murder, though the charges were eventually dropped. A frustrated, now unpopular political leader, he was later accused of conspiring to unite parts of the Louisiana Territory to form a new nation. For that he was tried for treason. Though acquitted, Burr’s heroic Revolutionary legacy was now sealed as one of infamy.

Through his trials and tribulations, Burr’s daughter Theodosia, who was S.C. Gov. Joseph Alston’s wife and our state’s first lady, defended her father. (If you’ve seen the musical, you’ll recall the ballad Burr sings to his infant daughter titled “Dear Theodosia.”)

After Burr went into a type of self-exile in Europe, Theodosia worked tirelessly from her 94 Church St. residence to restore his position and good name. In 1813, at age 29, she sailed from Charleston to comfort him in New York when her ship, the Patriot, was lost at sea. She was never heard from again.

Dueling remained legal in South Carolina until the 1880s, years after it had been outlawed elsewhere.

Sources and more information