WASHINGTON RACE COURSE

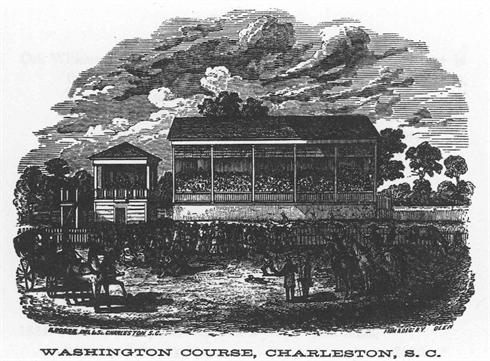

Like their namesake King Charles II, 18th and 19th century Charlestonians had few greater passions than horse racing. William Washington would be among the founders of the most prominent of Charleston’s 10 racetracks: the Washington Course, named after his cousin George. From its first race on February 15, 1792, until its interruption by the Civil War, the Washington Course was home to the crème de la crème of the South’s racing elite.

Racing played an important role in Charleston’s social life, where the South Carolina Jockey Club, America’s first, was organized in 1758. After the Washington Course was completed, the club’s annual Race Week, held each February, marked the pinnacle of Charleston’s social season. Here the great Lowcountry planters gathered to show their horses, make bets, attend a few balls, seal a few business deals, drink fine Madeira wine, and introduce their daughters to the right sort of people in the reserved seating section. Race Week was, as Jockey Club historian John Beaufain Irving described it in 1857, the "carnival of the state."

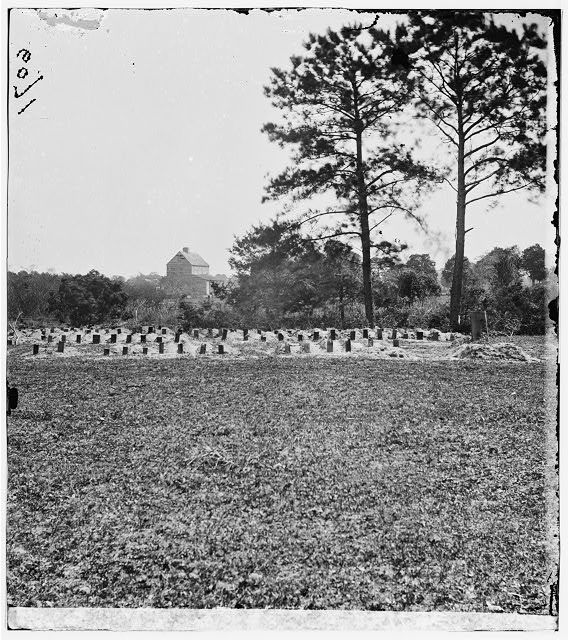

But the fun and games ended with the first shot of the Civil War just weeks after John Cantey’s mare, Albine, won the 1861 heat. The races took a hiatus, and the Washington Course was used to house Union prisoners of war. Officers were quartered in the Ladies Club, once the site of Charleston’s most gracious social affairs. Conditions in the open-air camp were horrendous; 257 Union soldiers’ deaths were recorded. They were buried within and around the racecourse in unmarked graves.

In 1875, the Jockey Club revived the races with more than 100 dues-paying members. Though money was tight, the Club still had two major assets: the track itself and a large cache of valuable Madeira wine that had miraculously escaped discovery by Union troops. Proceeds from the Madeira’s sale helped refurbish the racecourse.

Still, breeding racehorses is a rich man’s sport and few wealthy men were left in Charleston after the War. Grand balls and high style were no longer the order of the day. Race Week had lost its cache and attendance dropped. After its last race in 1882, the Jockey Club leased the racecourse, its surrounding pastures, and stables to a local farmer. On December 30, 1899, with about two dozen members left, the Club disbanded, donating their remaining assets, including the Washington Course, to the Charleston Library Society.

In 1900, the Library Society rented the land to the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, and later sold it to the City of Charleston. The footprint of the mile-long track still exists today, though paved. It remains a favorite of local runners, joggers and dog-walkers visiting the city’s Hampton Park.

America’s First Memorial Day

Charleston is one of several locales that claim to be the site of America’s first Memorial Day. That claim goes back to May 1, 1865, when thousands of emancipated African Americans marched in a parade to the Washington Race Course to exhume and respectfully rebury the bodies of the Union soldiers who died in the prison camp. They built a fence around the area with an arched gate that read “Martyrs of the Race Course.” They placed flowers on the graves, listened to speakers, and picnicked on the grounds to honor the memory of those who died fighting for their freedom. Many credit the freedmen’s ceremony at Washington Race Course as America’s first celebration of Memorial Day. The bodies were exhumed and reburied with honors in 1871 at military cemeteries in Beaufort and Florence.

Image at right: Augustus Belmont, a New York racing enthusiast, asked the City of Charleston to sell him the brick posts that marked the entrance gate to the old Washington Race Course, which had been inscribed by emanicapted slaves to honor the "Martyrs of the Race Course." The city gave them to him without charge. In 1905, he installed them at the entrance to his new Belmont Park racecourse on Long Island, where they remain today, visible as one exits the New Jersey turnpike.

Union officers were housed in what had been the race track's Ladies Club, the scene of many grand antebellum social affairs. (Photo: George N. Barnard, 1865, Library of Congress)

This pencil drawing on gray paper, c. 1860, illustrates some of the many Union graves found in and around the rack track, as also seen in the image below. (Image: Library of Congress, contributed by Alfred R. Waud; Photo: attributed to George Barnard, April 1865, Library of Congress)